[ad_1]

Documenting in the health record, especially in electronic health records (EHRs), is becoming an increasingly challenging task for many providers across the continuum of care. In recent years, many providers have become burned out and frustrated by EHRs, new reimbursement models, increased regulatory requirements related to quality, onerous query practices, and coding guidelines that vary by healthcare setting.

The purpose of this Practice Brief is to describe documentation best practices and serve as a resource in effective and efficient clinical documentation practices without having a negative impact on patient care. Providers should understand how their clinical documentation translates into data that is used for a variety of purposes.

For many years, providers have struggled with how to document clinical status to accurately report inpatient encounters, office visits, and other evaluation and management (E/M) services. With the use of EHRs in both hospitals and provider practices, “note bloat” and the use of cut/copy and paste has caused additional scrutiny on provider documentation. Furthermore, many providers are being queried for additional clarifications that may or may not be appropriate, causing additional documentation discrepancies within a health record. Providers are also frequently using checkboxes to meet documentation requirements, especially in the outpatient setting. As a result, it is very important for the providers to be educated on how to appropriately use these check boxes to avoid note bloat.

Documentation should also be reviewed and validated at the time of entry. The documentation should always be clear, concise, and to the highest level of specificity so that it paints the most accurate clinical picture. Although ICD-10-CM is used to report diagnoses in all settings, different guidelines apply for inpatient and outpatient settings, which may not be understood by providers working in both settings. ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting contains separate guidelines for inpatient and outpatient settings. For example, uncertain diagnoses documented as “probable,” “suspected,” “rule out,” or other similar terms demonstrating uncertainty can be coded in the inpatient setting but not in the outpatient setting.

See Table 1 for a quick overview of the ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting.

In the outpatient setting, providers are reimbursed for their professional services based on E/M codes. Providers rely on the 1995/1997 Documentation Guidelines for E/M Services. These guidelines assist providers in determining the most appropriate level of service to bill for their E/M services by providing guidance on what elements need to be included in their documentation. Provider documentation must support the history, examination, and medical decision-making (MDM). Providers can use either 1995 or 1997 documentation guidelines when selecting the appropriate level for the patient visit. However, they cannot use both guidelines. It is important for providers to remember that the selected E/M level must be medically necessary and supported by the documented condition/plan.

See Table 2 for a quick overview of the E/M services.

On November 1, 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized a provision in the 2020 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule. This provision includes revisions to the E/M office visit CPT codes (99201-99215) code descriptors and documentation standards effective January 1, 2021. This provision was finalized in response to provider burnout due to the administrative burden related to documentation requirements.

In an article published by the American Medical Association (AMA), the key elements of the E/M office visit overhaul include:

- Eliminating history and physical exam as elements for code selection. While significant to both visit time and medical decision-making, these elements alone should not determine a visit’s code level.

- Allowing providers to choose whether their documentation is based on MDM or total time. This builds on the movement to better recognize the work involved in non-face-to-face services like care coordination.

- Modifying MDM criteria to move away from simply adding up tasks to focus on tasks that affect the management of a patient’s condition.

An opportunity now exists for clinical documentation integrity (CDI) and coding professionals to incorporate this upcoming change into their provider education. Providers can be better prepared by having enough time to learn and understand how these changes might impact their current document practices before January 1, 2021.

Furthermore, telehealth services are increasing in popularity and there are more specific CPT codes that will define the amount of time spent on these services. There are CDI opportunities to ensure the time is documented appropriately and includes only the services allowed for coding and billing.

Reimbursement Methodologies and Quality Initiatives

The Medicare Claims Processing Manual Chapter 23 – Fee Schedule Administration and Coding Requirements Section 10.3 – Outpatient Claim Diagnosis Reporting also provides additional guidance on what types of diagnoses can be reported on outpatient claims. The rule of thumb is for providers to report a complete list of diagnoses that captures all the conditions that warranted the outpatient services. See Table 3 for an example.

Many providers may not be aware that the CMS-1500 claim form allows the inclusion of up to 12 diagnosis codes because they have been taught that only four diagnoses can be mapped to a specific CPT code. So why is it important for the providers to report additional diagnoses even though they are not going to link to a service (CPT code) line? The capturing of all diagnoses that are relevant to the treatment, socioeconomic, and/or psychosocial circumstances are important to accurately capture the patient’s clinical picture and potential health hazards, therefore providers should be educated on the impact of these additional diagnoses. For example, if a patient came in for an office visit for a cough and during the examination the provider documented that the patient is also treated with medication for diabetes and hypertension and has a history of right leg amputation status following a motor vehicle accident. These additional diagnoses may impact the patient’s overall risk score and treatment plan across the continuum of care, therefore it is very important for providers to be educated on the importance of documenting and reporting all diagnoses that are relevant and/or addressed during the visit and not to just report the four diagnosis pointers.

As already mentioned, accurate and precise provider documentation is more important than ever in the changing landscape of provider reimbursement and quality initiatives. Provider documentation burden has been debated and addressed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, but the need to capture the care of the patient remains. The new mantra is quality over quantity when it comes to documentation, but the concern will always be: Was the full picture of the visit captured to support the level of service that was coded and billed, chronic conditions addressed, and problem list updated? CDI and coding professionals can focus on areas related to coding and reporting as well as other documentation that supports quality initiatives to improve patient outcomes.

Providers who have practiced for years in their own office have been coding their services using charge capture forms or other methods to inform the billing staff of the services provided. With the consolidation of practices into large multispecialty clinics and hospital-owned practices, there are still physicians who code their own cases, and those who have professional coding support. Many larger facilities encourage providers to code their levels of service and procedures performed. However, the documentation of the MDM often lacks specificity that could support a higher level. This is an area where outpatient CDI can be of great value. Providers are also unaware of National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) edits and payer requirements such as the appropriate use of modifiers for the claim to be paid.

As the cost of healthcare premiums and copays have increased, many healthcare beneficiaries elected to enroll in managed care programs, which encourages efficient delivery of healthcare services. The traditional fee-for-service model has been declining in popularity by health insurers who have implemented varying types of managed healthcare plans over the years to decrease costs and encourage more efficient delivery of healthcare through risk sharing. The concern over this type of reimbursement was that quality of care was being sacrificed.

Enter alternative healthcare reimbursement models: The Affordable Care Act (ACA) ushered in a new era of healthcare that applies risk adjustment to patient populations and introduced value-based care. The term value-based care encompasses models such as risk sharing (capitation) with quality incentives, accountable care, population health, and bundled payments. These models provide incentives for providers to offer quality care at a lower cost. There are many facets to these models, but one point was clear in the literature, it requires engagement from providers, payers, and patients.

The ACA introduced a permanent risk-adjustment program (Section 1343). The risk-adjustment model is budget neutral and insurers covering healthier patient populations are required to contribute to a risk-adjustment pool that will help other insurers covering a higher-risk patient population. Higher-risk populations consist of patients with chronic conditions that require continuous treatment, monitoring, and maintenance. Providers need to be aware of the various risk adjustment models and rely on complete, timely, and accurate reporting of patient diagnoses. The accuracy of clinical documentation and reporting of these diagnoses may impact the patient’s/enrollee’s hierarchy, thus determining reimbursement. Risk adjustment methodologies assign families of diseases to a cost based on severity and projected use of resources.

It will be helpful to educate providers on hierarchical condition categories (HCCs). HCCs are made up of condition categories and the hierarchies are the compilation of related condition categories (CCs). HCCs were designed to predict resource consumption/healthcare costs of certain patient populations. The hierarchy consists of families of diseases that are assigned a cost based on severity of illness and projection of resource use. Theoretically, if a patient’s/enrollee’s chronic condition becomes severe, the patient will then require extra healthcare services. See Table 4 on for a snapshot of the many different types of HCCs.

As mentioned above, all risk-adjustment models depend on complete and accurate reporting of patient data. The clinical documentation in the health record must support the presence of all patient condition/diagnoses, along with the provider’s assessment and plan for management of each condition, especially chronic conditions. These documented conditions are then translated into reportable codes and this reported data is then used to predict costs for the following year for Medicare Advantage and/or commercial enrollees. Therefore, it is important for CDI professionals to educate providers on the impact of documenting non-specific diagnoses and the ramifications of not documenting chronic conditions. Providers need to be aware that their documentation can affect not only patient care and outcomes, but also reimbursement for future care due to risk adjustment. Providers should be validating and updating all documented conditions at each visit.

The medication list is also a great resource for CDI professionals who are validating diagnoses. Providers should be encouraged to document the condition being treated by each medication, demonstrating its relevance as a current and reportable condition. Educational efforts should also encourage providers to specify the acuity of every diagnosis, especially those only mentioned in the history of current condition section of the history and physical. Specifically, documentation should describe each condition as acute, chronic, exacerbated, or resolved to clearly convey its current status and relationship to the current episode of care.

Data Analytics

There are numerous opportunities now to extract data out of the EHR. For the data to be meaningful, the documentation of the care provided is an essential component of data analytics. Many EHRs now allow the provider to select their own diagnoses (example: drop-down boxes) with some of these diagnoses being identified as HCCs within the EHR. Therefore, providers need to be educated on how to appropriately select the most accurate diagnosis and to not select codes based on the first diagnosis that pops up and/or is identified as an HCC. Providers also need to be aware that their documentation is captured through many types of coded data including, but not limited to, ICD-10-CM/PCS, CPT, RxNORM, SNOMED CT, and Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC). This may go beyond the realm of the typical CDI professional’s role, but the documentation of the diagnosis and procedures performed is just as important. A CDI professional can also be a valuable part of an analytics team.

Suggestions for data use:

- Physician engagement in data analytics—they should be involved in ensuring data accuracy and leveraging it to make a difference when providing care to specific populations

- Validate whether listed medications have associated diagnoses

- Denial trends, medical necessity, documentation. As the Medicare Claims Processing Manual states, “Medical necessity of a service is the overarching criterion for payment in addition to the individual requirements of a CPT code. It would not be medically necessary or appropriate to bill a higher level of E/M service when a lower level of service is warranted. The volume of documentation should not be the primary influence upon which a specific level of service is billed. Documentation should support the level of service reported.”

- Claim edits and correct coding initiatives

- CMS measures the Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) improper payment rate through the Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) program. The three largest improper payment drivers are insufficient documentation, medical necessity, and incorrect coding. Collaboration between coding and CDI can address many of these issues at the provider level.

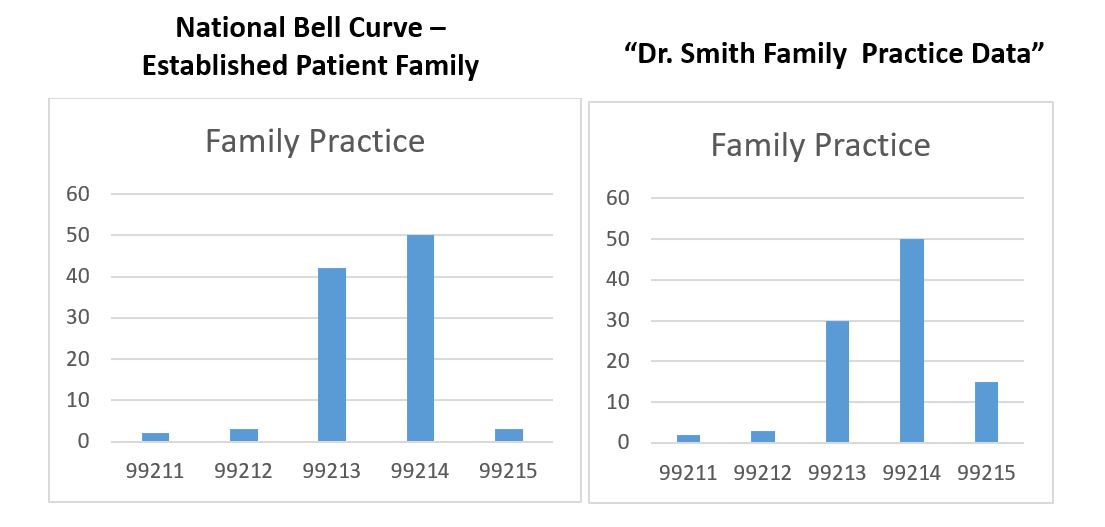

- Depending on the type of practice, such as specialty versus general medicine, E/M level distributions should be compared to national trends. A standard bell curve is not always an indication that physicians or coders are coding appropriately.

Additionally, healthcare data can be found in the following:

- Key performance indicators (KPI)/dashboard (for exam ples, see the online appendix for this Practice Brief)

- Quality indicators

- Care coordination/population health data. It’s important to identify key populations where there is risk, as well as social determinants of health for specific populations. Also important are chronic conditions—what are the most frequently documented conditions, and does documentation exist to show the conditions were addressed during a visit?

CDI Best Practices

Provider documentation may lack specificity and/or consist of conflicting documentation. Therefore, it is vital for hospitals and provider practices to have a query process in place to ensure providers have the opportunity to add or clarify documentation in the health record in a compliant manner. Queries, whether performed verbally, by paper, or electronically, serve the purpose of supporting clear and consistent documentation of diagnoses during a patient’s visit. Professionals performing the query function should maintain a compliant query process. According to the AHIMA/ACDIS Guidelines for Achieving a Compliant Query Practice (2019 Update), all queries, including verbal queries, should be documented in writing to demonstrate compliance with all query requirements to validate the essence of the query. Regardless of how the query is communicated, it needs to meet all of the following criteria:

- Be clear and concise

- Contain clinical indicators from the health record

- Present only the facts identifying why the clarification is required

- Be compliant with the practices outlined in this Practice Brief

- Never include impact on reimbursement or quality measures

Although verbal queries may be prevalent in the physician practice setting due to the close working relationship and quick turnaround of patient visits, it is important to follow guidance requiring their recording. According to the Practice Brief, verbal queries should “include documentation of the conversations that occur with providers regarding documentation of reportable conditions/procedures. Conversations should be non-leading, include all appropriate clinical indicators, and include all plausible options. In capturing the essence of the verbal discussion, timely notation of the reason for the query (exact date/time and signature), clinical indicators, and options provided should be recorded and tracked in the same manner as written queries and be discoverable to other departments and external agencies.” Provider response to the query must be documented in the permanent health record in order to be coded.

Professionals issuing queries must adhere to the following guidelines:

- Do not lead the provider to a certain diagnosis

- Include appropriate clinical indicators to support the query

- A query may be initiated to clinically validate a diagnosis that a prior health record provided evidence to support particularly when clarifying specificity or the presence of a condition which is clinically pertinent to the present encounter supporting accuracy of care provided across the healthcare continuum. Prior encounter information may be referenced in queries for clinical clarification or validation if it is clinically pertinent to the present encounter. However, it is inappropriate to mine a previous encounter’s documentation to generate queries not related to the current encounter.

Please refer to AHIMA/ACDIS’s “Guidelines for Achieving a Compliant Query Practice (2019 Update),” available online in AHIMA’s HIM Body of Knowledge at bok.ahima.org, for additional details on writing compliant queries, including query examples.

Providers frequently benefit from tailored education that they can relate to. The education should include examples and/or illustrations of best practices, along with their current documentation practices and areas of improvement. The following tasks should be considered by the CDI team in both the inpatient and outpatient settings (for example, a large physician practice) when putting together an education program for the providers:

- Perform concurrent reviews and offer providers feedback to improve completeness and specificity in documentation to support ICD-10-CM/PCS, CPT, and HCC coding

- Conduct chart reviews and any necessary provider education for compliance with quality reporting initiatives

- Perform retrospective chart reviews for coding compliance and quality measures

- Collaborate with team members to aggregate findings from clinical documentation reviews (both retrospective and concurrent) and design educational content and remediation strategies for both individual providers and provider groups

- Coach the provider on opportunities for improving clinical documentation based on annual compliance review findings

- Collaborate with team members on ways to improve EHR functionality in support of clinical documentation coding trends and requirements

- Translate feedback from providers, CDI professionals, coding professionals, and compliance into content enhancements in the EHR

- Design, test, and implement revised drop-down menus and other enhancements to assist providers in improved documentation and coding completeness

- Collaborate with providers to improve existing standard note and template functionality

- Collaborate with the EHR vendor to validate the embedded clinical terminology system within the EHR is appropriately mapping to the correct ICD-10-CM and/or SNOMED CT codes

- Prepare physicians for the documentation changes effective in 2021

- Review times documented for telehealth services

- Schedule, prepare, and lead meetings with practices focused on documentation, coding, and quality performance gap closure, and develop and implement follow-up activity

- Lead or provide education/training to clinical care (providers, nurses, etc.) and administrative support team members regarding the clinical documentation requirements

Documentation Education is Vital

It is vital to educate all providers on the importance and significance of the integrity of their documentation along with the many reimbursement methodologies and coding guidelines and the changes on the horizon. Providing a snapshot from a high-level perspective will help providers gain a better understanding on the importance of documentation across the continuum of care. Healthcare organizations should leverage their coding and CDI professionals to provide this type of provider education. Despite the differences of documentation needs, one message that applies to all settings is that providers should always document to the highest level of specificity (e.g., acuity, chronicity, etiology, etc.) and be as accurate as possible in their initial documentation. With this level of specificity and accuracy, all requirements for coding purposes and quality reporting will fall into place while reducing the volume of queries. Providers should be viewing coding and CDI professionals as their documentation educators. A proactive delivery of provider education tailored to assist them in learning the art of documentation integrity will benefit all stakeholders.

Notes

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Publication 100-04, Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf.

References

American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA). “Guidelines for Achieving a Compliant Query Practice (2019 Update).” http://bok.ahima.org/doc?oid=302674.

AHIMA. AHIMA Outpatient Query Toolkit. 2019. http://bok.ahima.org/PdfView?oid=302735.

American Medical Association (AMA). AMA Table 2 – CPT E/M Office Revisions Level of Medical Decision Making (MDM). www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf.

AMA. CPT Evaluation and Management (E/M) Office or Other Outpatient (99202-99215) and Prolonged Services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99XXX) Code and Guideline Changes. www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf.

Barnette, Erin et al. “Evolving Roles in Clinical Documentation Improvement: Physician Practice Opportunities.” Journal of AHIMA 88, no.5 (May 2017): 54-58. http://bok.ahima.org/doc?oid=302135.

Benz, Laurie and Christine Polene. “Don’t Let Data Become a Monkey Wrench to Your Outpatient CDI Efforts.” CDIS November 2019. Outpatient CDI Symposium. November 21, 2019.

Bonner, Dari and Karen M. Fancher. “Expanding CDI to Physician Practices: Five Documentation Vulnerabilities to Address in 2016.” Journal of AHIMA 87, no. 5 (May 2016): 22-25. http://bok.ahima.org/doc?oid=301436.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/10cmguidelines-FY2020_final.pdf.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2018 Medicare Fee-for-service Supplemental Improper Payment Data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Medicare-FFS-Compliance-Programs/CERT/Downloads/2018MedicareFFSSuplementalImproperPaymentData.pdf.

CMS. CMS Evaluation and Management Services. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/eval-mgmt-serv-guide-ICN006764.pdf.

Hess, Pamela. Clinical Documentation Improvement for Outpatient Care: Design and Implementation. Chicago: AHIMA Press, 2018.

Robeznieks, Andis. “E/M overhaul aims to reduce physicians’ documentation burdens.” American Medical Association. November 1, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt/em-overhaul-aims-reduce-physicians-documentation-burdens.

Prepared By

Lisa Hart, MPA, RHIA, CDIP

Anny Pang Yuen, RHIA, CCS, CCDS, CDIP, Approved ICD-10-CM/PCS Trainer

Acknowledgements

Patty Buttner, MBA/HCM, RHIA, CDIP, CHDA, CPHI, CCS, CICA

Tammy Combs, RN, MSN, CCS, CCDS, CDIP

Lisa Crow, MBA, RHIA

Cheryl Ericson, RN, MS, CDIP, CCDS

Patricia Maccariella-Hafey, RHIA, CDIP, CCS, CCS-P, CIRCC

T.J. Hunt, PhD, RHIA, CDHA, FAHIMA

Tiffany Ortiz, BSHA, RHIT, CCS, CCS-P

Kathleen Peterson, RHIA, CPHI, CCS, MS

Melissa Potts, RN, BSN, CCDS, CDIP

Donna Rugg, RHIT, CDIP, CCS, CCS-P

Margaret Stackhouse, RHIA, CPC

Mari Pirie-St. Pierre, RHIA

Leave a comment

[ad_2]